3 What is peer review?

Peer review is often considered to be the ‘gold standard’ of science (Mayden, 2012). Manuscripts that have passed peer review are often considered to have been scrutinised to the highest level. If one’s peers in the scientific community consider that a manuscript is worthy of publication, then it meets the high standards of peer review. In theory, the review of peers acts as the gatekeeper to all that is good in science, and excludes all that is bad. A lot has been written about peer review (>23000 articles!), and there’s plenty more to read out there (Eve et al., 2021).

While the views in the above paragraph are generally held, there is also a universal acknowledgement that there are a lot of problems with peer review. That this has been widely acknowledged is probably an understatement, as most people who have experienced would likely already know. These problems will be address in another chapter in the last section of this book. The myriad of failures means that peer review shouldn’t ever be exulted as the ‘gold standard’ touted by many publishers. Peer review does provide a filter of sorts, with the result being better considered as a ‘silver standard’.

But peer review is here to stay and will remain as a fundamental aspect of publishing, and so there are several chapters in this book that are dedicated to different aspects. In this chapter, I attempt to explain what peer review is. Elsewhere there are descriptions:

- what to expect from peer reviewers

- how to respond to peer review

- how to conduct peer review

- problems with peer review

This chapter provides an overview of the topic, but you may need to refer to the other chapters first depending on what your current need is.

## History of peer review

The history of peer review is surprisingly modern. We have already seen that journals themselves only date back to the 17th century (see chapter in Part IV). These journals included a form of peer review in that letters concerning studies could be published, along with comments made at presentations. However, the type of systematic enforced peer review described in this book is very recent (Eve et al., 2021). The journal Nature for example only started systematic peer review for its articles in 1973, and mainstream editor led peer review only really started in the late 1940s (see Tennant, 2017). Typical society journals have followed a similar form of evolution from newsletters to scholarly journals (Measey, 2011).

3.1 How high is the peer review bar?

It is difficult to emphasise how high the peer review bar is. When your manuscript is scrutinised by your peers, it is very rare (practically unheard of in the careers of most researchers) that it will get accepted without modifications. This is because the experience of academics tends to be so wide, and vary so much from individual to individual, that it is almost impossible to predict what a peer reviewer will see when they read your manuscript.

You should expect that your manuscript will not receive an easy ride through peer review. But you should also expect that it will be improved. As we will see later, this improvement might not be immediately obvious to you when you first read the comments.

It is also important to note that as the author, you are the net beneficiary of the peer review process, and that once you press the submit button (free for the vast majority of us, but see part IV), a cascade of events happen, all of which are done in the name of you and your submission. It stands to reason then that you should be sure that your manuscript is as ready as it can be for submission.

3.2 Who are your peers?

Essentially the peers in peer review are people that editors find and persuade to conduct the peer review. It can be difficult to find people to conduct a peer review. Although only two or three reviews are needed sometimes as many as 20 or 30 individuals can be approached. Perry et al. (2012) lamented on the increasing difficulty in persuading colleagues to conduct peer review of manuscripts. This difficulty is growing as the number of manuscripts increases, prompting some (particularly those trying to find reviewers) to suggest that we are reaching a crisis (e.g. Chloros, Giannoudis & Giannoudis, 2021). In fact, what is needed is a better distribution of peer reviewers - many academics are simply never approached as they are not known to editors or their bias inhibits from asking. With a doubling time of 15 years (Bornmann, Mutz & Haunschild, 2021), we will approach a natural ceiling. But for now there is plenty of wiggle room, and the real problems with publishing continue to obscure actual difficulties from those perceived by frustrated associate editors.

While your ‘peer’ might sound like someone who is in an equivalent position to you, this may well not be the case. If you are junior, your peer reviewers may be very senior. Equally, senior authors may have peer reviewers that may be very junior. Does this make a difference? For some people it might, especially when they know the other party and assign some level of competence associated with their seniority. Of course, both junior and senior researchers are capable of getting points in peer review wrong, just as both are also capable of providing insightful feedback. The editors are those in the hotseat about what it all means.

3.2.1 Professionals

Peer reviewers are normally professionals. Academics postdocs or postgraduate students. Occasionally there are specialist amateurs who have very high academic standards and who can be contacted to conduct peer review. For journals with a special remit, industry professionals may be approached to provide feedback on applied aspects of manuscripts.

3.2.2 Scholars

Peer reviews should be familiar with the subject area to a good level of scholarly achievement. Undergraduates and many postgraduate students would not be considered eligible by many editors as selection for peer review. Personally I found that many PhD students, especially those in their final stages of studying are very good peer reviewers.

3.3 The role of the editor

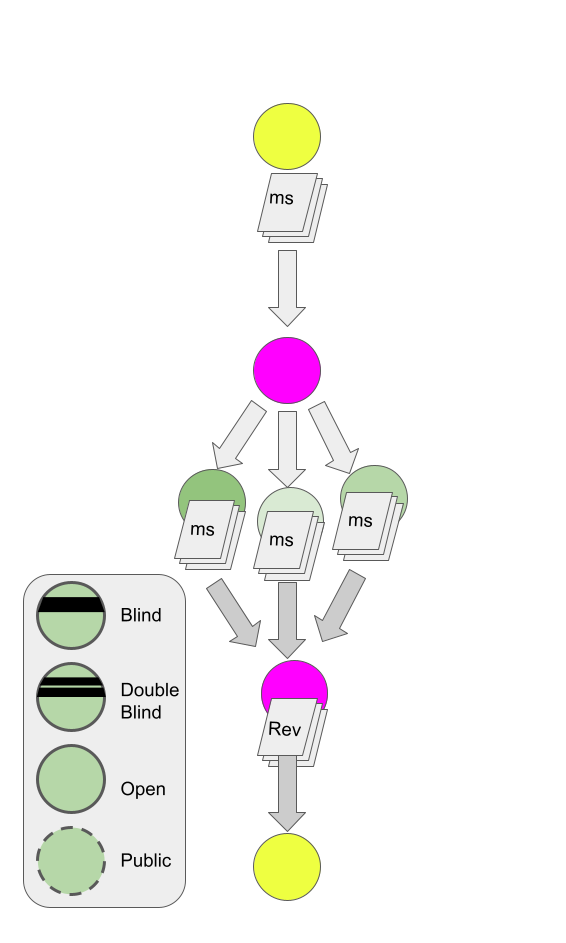

The editor has an important role to play (see Figure 3.1):

- To assess your submission

- Does it align with the journal?

- Is it sound enough to send to peer review?

- Whether to use a specialist associate editor

- To choose the peer reviewers

- Without potential conflicts of interest

- Who can cover the content of the manuscript

- Who agree to doing the review within the prescribed time-frame

- To assess the reviews of the reviewers

- Mitigate for potential bias in the reviews

- Judge what is in the manuscript against what reviewers have found

- Determine whether sufficient merit remains in order to undergo a decision (including more peer review)

- Write the decision: When you bear in mind that the decision is likely to involve some arbitration between different reviewer opinions, and to direct the authors about what changes need to be made to a ms in order to make it acceptable, the decision is not a simple exercise. Making an editorial decision will require careful reading of the manuscript, as well as looking past potential biases of reviewers.

3.4 Who are the Gatekeepers (Advisory & Editorial Boards)

The Advisory Board (sometimes referred to confusingly as the Editorial Board) together with the editor and associate editors, make up the gatekeepers of scientific knowledge. Through their combined influence, they determine what knowledge is published by screening submissions and allowing only a proportion of them to be published. The Advisory Board are invited academics who are often considered to be leaders in the field relating to the journal subject area, and are invited to join by the editor and/or the society. In theory, they are ambassadors for the journal, encouraging authors to submit their manuscripts (for example following talks at conferences), identifying new topics for editorials and special issues, and generally supporting the editor and associate editors. The Advisory Board are also there in the case of dispute (especially between authors and editors), or for complaints coming from third parties (against editors or published articles). In general, most issues involving a journal are dealt with by the editor. Only in exceptional circumstances are the Advisory Board consulted. Practically, the role of the Editorial Board is largely passive, and hence many think of the gatekeepers as being only the editor and associate editors.

Here, I refer to the editor and associate editors collectively as the ‘Editorial Board’.

The editorial board are said to support orthodox views in their fields and could be thought of as representing the ‘establishment’ (Crane, 1967). The argument continues that like supports like, and that editorial boards in science tend to be composed of white men at US universities. One real problem with gatekeepers is their lack of diversity (Potvin et al., 2018). In a study of 250 science journals, only one country on the African continent had gatekeepers represented at 0.16%, while the USA had 53.87% of the gatekeepers (Braun & Dióspatonyi, 2005). Increasing the geographic diversity of the editorial board leads to an increase in the diversity of the authors (Potvin et al., 2018; Demeter, 2018; Goyanes & Demeter, 2020), something as biologists we can all appreciate a real need for.

Editors, sometimes referred to as editors-in-chief (presumably to distinguish them from associate editors) are usually alone in their position at journals. Increasingly, journals with large numbers of submissions have joint editors-in-chief, or even another tier of editorial oversight under the editor-in-chief. The major part of their job is screening the submissions to the journal and assigning the most appropriate associate editor. In most journal models, they review the information provided by the associate editor and make a final decision on whether or not a manuscript is accepted to the journal (see Figure 18.1). Their gatekeeping role comes with the many decisions that they have influence over, for example what kinds of articles they will accept, the decision to amend the description of the journal on the website, which will impact how you choose your journal. This is the reason why you are always advised to look at the current content of your journal choice. There is also the important role that the editor takes when things go wrong, which can be very time consuming.

Associate Editors are most likely to be tenure-track faculty in a US research intensive university, according to an illuminating study by Kelsey Poulson-Ellestad and colleagues (2020).Most are within 10 years of earning their PhD, and are therefore still Early Career Researchers, and have published ~20 papers and conducted >50 reviews. Rewards include a better understanding of the publication system, improved communication skills, keeping current in the journal area and giving back to the scientific community. Most of the costs involved time around finding reviewers, reading manuscripts and making difficult decisions, especially around conflicting peer review comments. But editing takes time, and can be burdensome in this respect especially for Early Career Researchers who have so much else on their plate. The advice of many Associate Editors in the study was for others not to take on editing unless they are sure that they can commit enough time (Poulson-Ellestad et al., 2020). Gender equality in Associate Editors of ecological journals has been improving over time, as has the gender equality of reviewers (Fox & Paine, 2019), although other surveys have found huge disparity of only 16% of subject editors being women in 10 environmental biology and natural resource management journals (Cho et al., 2014). However, women are more likely to refuse an invitation to become an Associate Editor (Fox & Paine, 2019). The gender imbalance in gatekeepers is indicative of the general imbalance in gender across STEM subjects (for more studies see here).

FIGURE 3.1: A simple schematic for one round of peer review. In this figure, you (yellow circle) start by submitting your manuscript (ms) to an editor of a journal (pink circle), who assesses it and send it out to 3 reviewers (green circles). Each reviewer independently generates an opinion in the form of a review (rev). They each pass this back to the editor, who then makes a decision on your ms. Each light grey arrow going out may be quite quick (a few days or weeks), but the dark grey return arrows might take a long time (often counted in months). Reviewers come in different flavours (see below), generally at the discretion of the editor.

All of the processes in Figure 3.1 need to be worked around the editor’s existing job, professional and research commitments (i.e. the day job), and their home life. The motivations for shouldering this additional work-load will be as individual as there are people in these roles. However, I have summarised some of the acknowledged motivations in Table 3.1.

| Motivation | Editors | Associate editors | Board member | Reviewers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The prestige associated with the journal | X | X | X | - |

| Increasing their professional network | X | X | - | X |

| Increase their soft power | X | X | - | X |

| Participate in the production of knowledge | X | X | - | X |

| Give back to a system in which you’ve benefited | X | X | - | X |

| Part of obtaining tenure | - | X | - | X |

| Editors-in-Chief are usually selected from among the ranks of the Associate Editors | - | X | - | - |

| A better understanding of the publication system | - | X | - | - |

| Keeping current in the journal area | X | X | - | X |

| Prestige of having your name listed on the journal website | X | X | X | - |

| An opportunity to use soft power at conferences and other meetings | X | X | X | - |

| Recognition of being influential in your field | X | X | X | - |

| Another lever to use in arguing for promotion | X | X | X | - |

| Complimentary access to the journal | - | - | X | - |

3.5 Reviewer models

Reviewers themselves come in different flavours that are (mostly) predetermined by the journal regulations.

3.5.1 Blind reviewers

Blind reviewers know who the authors are, but are anonymous to the author, but known to the editor. This can be considered the ‘standard model’ in peer review. There are plenty of problems with this model as reviewers may use their anonymity to hide their biases and are even known to become abusive. Although reviewers may be anonymous, sometimes communities are so small that authors might guess who these people are, simply by their comments and suggestions. Although this is the most common type of review format it is the least recommended. If you feel that there may be potential reviewers who bear a grudge to your laboratory, your institution or your work then it may be better to avoid this kind of review system.

3.5.2 Double blind reviewers

Double blind reviewers do not know who the authors are, and are anonymous to the author, but known to the editor. The double blind model was conceived to remove some of the potential biases (particularly around gender, nationality and race) that might come about through the identification of the authors and their addresses. Again, it has been mooted, and it is my also experience, that in a small community one tends to know who authors and reviewers are simply by the subject of the manuscript and the comments (see also Eve et al., 2021). However, even when groups can be identified, it is not always possible to determine the author or author combination, and so biases around gender and race may still be avoided with this model.

3.5.3 Triple blind reviewers

In theory, it is possible for the editor, after having chosen the reviewers, to be blinded from their identity once they submit their review. This may prevent the editor putting more importance to a more senior reviewer, and ignoring more junior viewpoints.

3.5.4 Open Peer Review

In Open Peer Review (OPR) authors know who reviewers are, reviewers know who authors are, and reviews alongside rebuttals are published with discrete DOIs together with a published manuscript. It should be noted that manuscripts that are not accepted never have their review history published, an important flaw in the system that we will return to later. This description of Open Peer Review refers to only one (most transparent) variant, and there are at least 22 subvarients available in the literature, and a lack of common definition (for a thorough discussion see Ross-Hellauer (2017)). For example, some reviewers can still choose to remain anonymous in many publications (although authors cannot - for obvious reasons), and some journals force reviewers into double-blind reviewing and then publish their comments anonymously as Open Peer Review. Other publishers allow any volunteer reviews or comments to be published alongside an article. Hence Open Peer Review generally means that reviews and comments are published alongside the article with varying degrees of reviewer anonymity. Note that it can be very difficult to find reviewers who are prepared to reveal their names to authors (see Delikoura & Kouis, 2021), ~40% at PeerJ.

A mixture of OPR and closed reviews in the same journal allows the benefits of OPR to be studied. A study that compared PeerJ publications in which reviews were made public, compared to those that authors chose to keep closed, suggested that the subsequent number of citations increased by a third for OPR model (Zong, Xie & Liang, 2020). While another study found no improvement in citations for articles published in Nature Communications (Ni et al., 2021). Yet another study of PLoS publications found a positive association between the OPR model and higher article page views, saving, sharing, and a greater HTML to PDF conversion rate, but no benefit to citations (Wei et al., 2023). Wei et al. (2023) also noted that the citation index used changed whether positive benefits were found or not.

It is only possible to speculate about why more sharing and citing may be a result of OPR. The decision at PeerJ to open reviews is made first both by reviewers (who opt not to be anonymous), and then by authors (who opt to open reviews). In studies where both groups co-operate, we might hope that this results in a higher quality product. Indeed, public reviews tend to be longer, although positive comments are more frequent in closed reviews (Bornmann, Wolf & Daniel, 2012). It is equally possible that authors who choose to open their peer review are more progressive and active within research (leading to more citations).

OPR could be considered the most transparent system for any journal. It has also been called Open Evaluation (OE) by Kriegeskorte et al. (2012). PeerJ PLoS and eLife are among a very small handful of journals that have tried to instigate this model. Interesting developments of this model have seen PeerJ drop the option for authors to decline OPR as of February 2023, and eLife drop the rejection of manuscripts that are reviewed as of March 2023 (Abbott, 2023), alleviating the problem noted above.

The OPR model does encourage good behaviour (or the avoidance of some of the worst problems) on the part of reviewers. However, reviewers remain brutally direct even when they are named, such that even open comments may be construed as bruising by the authors (Eve et al., 2021). Another downside to OPR is that there is still the potential for bullying behaviour if reviewers know who authors are when conducting a review (see Part IV). This is then aggravated by bullies who also choose to remain anonymous, and can only be mediated by insightful editors. A solution for this might be a double-blind reviewing model followed by Open Review Publishing of comments and rebuttal. This would encourage reviewers to interact with the publication after review and might alleviate some potential for bullying. I am not aware of this model being practised by any journal in the Biological Sciences today.

3.5.5 Public reviews

Public reviewers know who the authors are, and are known by the authors and editor, and their names (and often their reviews) are made available to the public. This model is relatively recent, and comes along with the possibility of making the reviews with their own DOIs available along with the accepted manuscript. It is worth noting that, to date, reviews for manuscripts that are rejected do not get posted using this or any other current publishing model. It does exist in the world of preprints.

3.6 Learn more about peer review by doing it

As an early career researcher, you may well be asked to conduct peer review of an article in your specialist field. If you have never been asked, then tell your mentor to recommend you. Usually when they turn down an opportunity to conduct peer review, they have an opportunity to name someone else. If you have told them that you want some manuscripts to review, it should be straightforward for them to add your name when appropriate.

Another option is to volunteer to conduct peer review for an independent peer review site, like Review Commons or Peerage of Science. Here you can register your interest and then take your pick of articles that get submitted. A nice aspect is that Review Commons have Referee Cross-commenting, so that you get to see the other reviewer comments and make additional comments on these as you see fit. Review Commons and Peerage of Science are both excellent platforms on which to get some experience with reviewing.

Similarly, you could post your reviews of preprints online. You might be shy to do this at first, so consider sitting with a lab mate and doing a review together. You can always ask your mentor to take a look at your review if you are unsure whether or not it should be posted publicly.

When you register in the editorial manager software for journals that you submit to, there is often an option to state what areas of your field you are particularly specialised in, and whether or not you are interested in conducting peer review in these areas. This is also worth doing if you want to generate requests for conducting peer review.

Another way of getting noticed to to sign up to society training programmes for peer review. These might happen at conferences, or could be through web based courses. Although it should be noted that such courses may have little impact to improve your peer review (Schroter et al., 2004), you will certainly gain more insight. You will need to register to conduct such training, with the result (sometimes) that your name will be entered into the editorial management software, together with your trained status. Some courses actually have ‘live’ mentors who read through and critique reviews that you conduct. All of these are a good idea, but be sure to check out the time commitment required before you start.

Good reviews get noticed by editors, and it is a good way of increasing your network through soft power.

We will look in more detail about how to conduct peer review later in this book.

3.6.1 What do peer reviewers get out of participation?

Table 3.1 suggests that reviewers receive the least out of the system for their efforts. Having simplified this in the table, there are lots of exceptions, and certain journals do provide incentives for reviewers, including free access to their content. Doing a good job of peer review will generate soft power if you renounce your anonymity. Doing this for a journal where your name is displayed alongside the article will help increase your profile.

Note that what reviewers get out of participating in peer review is almost identical to editors (see Table 3.1). Editors benefit at a higher level, mostly as their names are seen more often by more people, but with the drawback that they do a lot more work than the peer reviewer.

I have heard some members of the community claim that they will continue to accept peer review requests until these cover what they are demanding of the community (i.e. reviews offered per year = submissions per year x ~2.5). Although this sounds very fair, I would suggest that the reality is more subtle. You shouldn’t be accepting to conduct peer reviews for articles where you feel that you lack specialist knowledge. Neither should you be conducting peer review when you feel that you have a conflict of interest.

If you do have to turn down the invitation of peer review, then do it as soon as possible, and try to suggest someone else that you think could do it.