1 The transition from closed to open

There are a lot of problems in publishing in the biological sciences, but it doesn’t have to be this way. The aim for this book is firstly to help you navigate the current ‘closed’ system (while acknowledging that parts are already open), and act as a catalyst toward a more open, transparent and equal system for the future not only of publishing science, but permeating throughout the culture of the scientific project. We have all the tools to make this transition now, and I think that this change will likely come within the time frame of the careers of you as an Early Career Researcher. But as you will see, this change needs to be driven.

While I’m going to pitch the transition from closed to open publishing as a simple process, and as a move from darkness into light, I acknowledge that it might best be defined as a wicked problem. I hope that a lot of these complexities will come out in the book, but acknowledge that a lot will be left unsaid. A large unanswered question is what happens to all the downstream impacts of changing a lucrative academic publishing business that employs tens of thousands of people. I like to think that many of these skilled people, who themselves are not recipients of the large fees acquired by the publishers, would be absorbed into the repurposed institutional libraries. No doubt, there will be casualties. But my belief is that the importance of the scientific project, and the wicked problem we currently face in academic publishing, far outweighs the problems that we will see during the transition.

Throughout this book, I will make reference to the ‘scientific project’ as a broader philosophical stance in which our studies in biological sciences is simply a part (see Measey, 2021). This is a stronger institution without the culture of assumed knowledge and elitism that we see today. I consider movement away from the current model of publishing to be at the heart of this essential institutional transformation. Such a movement involves both bottom up changes, made by you as a researcher (such as starting an Open Science Community), and top down changes made by funding agencies, academic institutions and gatekeepers.

1.1 Three fundamentals of publishing in Biological Sciences

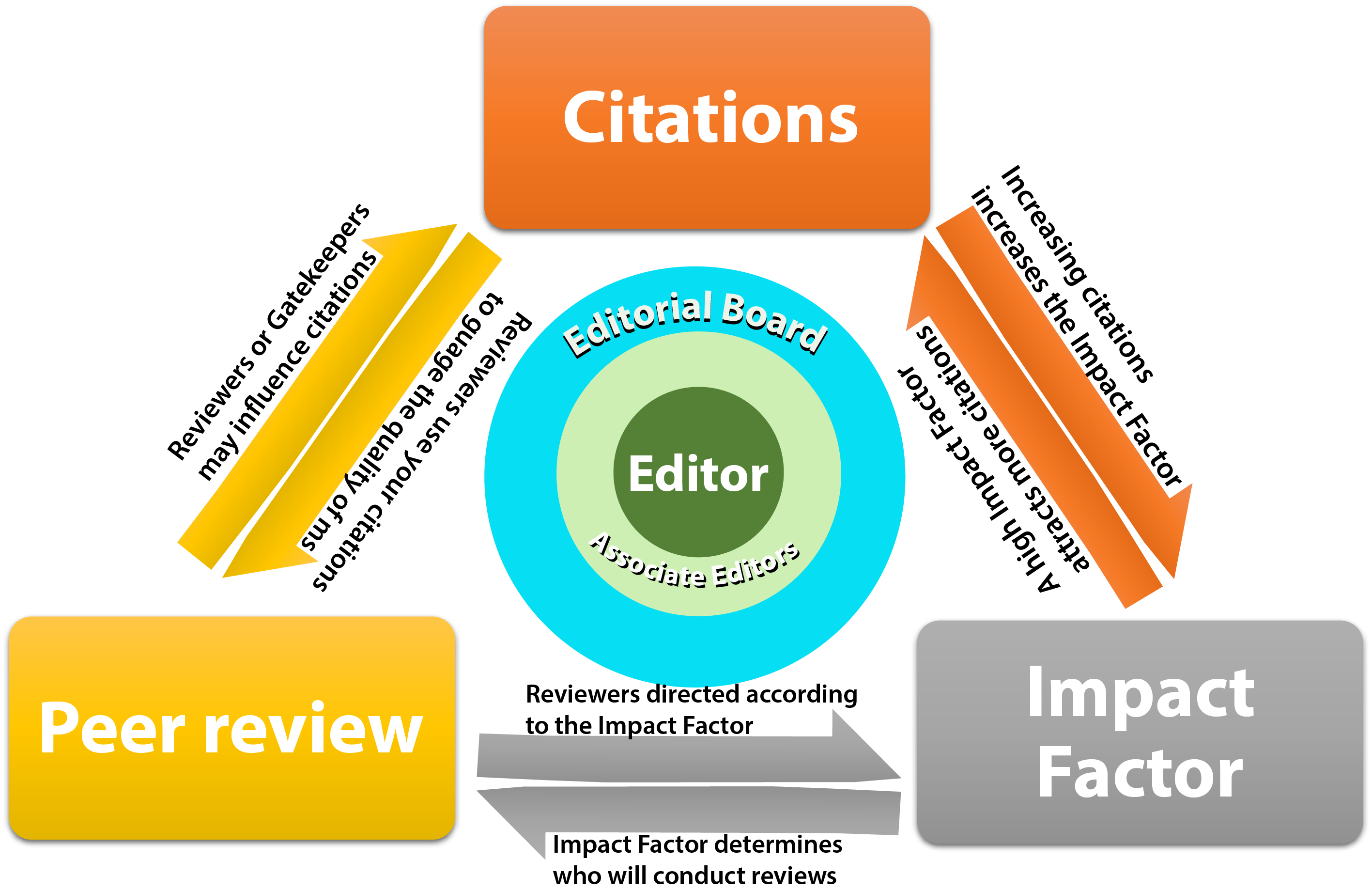

There are three fundamental concepts that lie at the heart of understanding of current publishing models in the Biological Sciences (Figure 1.1). In themselves, none of them should be particularly influential as they don’t relate to your study, how well the study was done, or what your results were. Nevertheless, these three aspects of publishing are key in your understanding of the nuances of publishing, and your understanding will likely make the difference between publishing your work being an obstacle that is occasionally insurmountable, and finding your way with a lot more ease through the process.

1.1.1 Gatekeepers

The journal editor is the kingpin, and sits at the centre of this triangle, and has the power, backed by their gatekeeping advisory board and associate editors, to continue the current model, or oversee the change. Editors make decisions, not simply whether to accept or reject your manuscript, but also to implement policies that take their journals in one direction or another. In some models, they are given this power (usually democratically) by the scholarly society that they represent, and oversight is granted by an editorial board who mediate in any dispute, but also in theory have influence over the editorial policy. Editors appoint associates that handle many of the manuscripts that are submitted, shuffling them between reviewers and authors until they feel that they are worthy of publication (or not). These associate editors are also responsible for implementing the policies of the editor, the editorial board, and the scholarly society. In models where there is only a (for-profit) publisher, the publisher appoints the editor and together they appoint the editorial board. In both models, the editorial board, editors and associate editors are thought of as being the gatekeepers to the scholarly integrity that permeates scientific publishing. There is more information on the advisory and editorial boards in Part I.

FIGURE 1.1: A simple schematic for the three fundamentals of publishing in the current Biological Sciences model. Citations, peer review and impact factors each have direct impact on each other and your understanding of each one and how they relate to the other will be pivotal in clarifying your understanding of how to publish your work. At the heart of the process are the gatekeepers: Editorial board, associate editors and the editor.

Gatekeeping takes a lot of time and effort, and there are plenty of places where the current system lacks the transparency that is needed. In theory, there’s nothing wrong with this model, were it not for some for-profit publishers that have used the system for their own gain. Instead of the gatekeepers focussing on science, they have become distracted by metrics and hype promoted by publishers. Each of the three facets that surround the gatekeepers in the current publishing model (Figure 1.1) need to be changed to open up the system for a more equitable future, and eliminate the current biases that favour the select few.

1.1.2 Is it possible to do without the publishers?

Editors don’t have a complete free reign over what to do with their journal. They may be constrained by the publishers, if their journal is run on a for-profit model, or by a contract with a publisher, for most society journals. Journals which are independent of societies and publishers are very rare, but do exist. However they work, editors sit as king-pins of the system. There are examples of editors who have taken all of their associate editors and authors and moved their entire platform to a not-for-profit system. This has also meant changing the name of the journal, as the publisher often owns this. The first example, that I’m aware of, happened in 2015 in the social sciences where the editor of Lingua walked away from publishers Elsevier (see Baković, 2017). As Elsevier owned the name, the editor, Johan Rooryck, started a new Open Access journal Glossa. There was a fight (see Rooryck’s website), but Rooryck showed that it could be done, and has therefore paved the way for others. Not only did Rooryck show proof of concept, but he formed the Fair Open Access Alliance, who have managed to pull 6 titles away from Elsevier since Lingua flipped. Most recently, the entire editorial board of the prestigious biosciences journal Neuroimage stepped down in protest against Elsevier’s refusal to moderate their Article Processing Charge. The editorial team have decided to set up their own non-profit Open Access title.

“Elsevier preys on the academic community, claiming huge profits while adding little value to science. All Elsevier cares about is money… They just got too greedy. The academic community can withdraw our consent to be exploited at any time. That time is now.”

Prof. Chris Chambers (2023), former editorial team of Neuroimage

It is important to add here that when the gatekeepers leave, the publisher simply approaches new people to take over, and the old journals remain alongside the new. The problem that Chambers and other academics who leave big publishers is that they don’t own the journal title, and with that comes the metrics that pull in many authors who rely on publishing there for their careers. If the editorial board resigns, the publisher simply approaches another set of academics who quickly jump on-board. It appears that there is no shortage of academics who are prepared to step into the shoes of editors who part company with the publishers, due to the perceived prestige of being a journal editor. See what draws editors in here.

All editors are answerable to their advisory board, and to the scholarly society from which they were (usually) voted into office. The society (often through the editor) signs a deal with the publisher, and this usually runs for a period of 5 years (see Part IV). Society journals usually own their own content and title, and so can decide to leave the publisher whenever their contract expires. It just takes will power, and being prepared to say goodbye to that income stream.

So why do the gatekeepers stay with the publishers? It’s mostly smoke and mirrors. Editors and gatekeepers in general are busy people. Their gatekeeping roles are not their primary jobs (for the most part), and if they are then the publishers are paying their wages. What they are most interested in is a smooth system that works with minimum effort on their part. This is what the publishers have established so well, and the principle way in which they will try to persuade gatekeepers to stay with them. Next is the money, which flows from the publishers into the accounts of the societies, with occasional small amounts to editors (and in rare cases associate editors) as expenses. Such perks used to be more substantial, like trips to conferences, hotel stays and wining and dining. But I understand that this is largely gone now. The perceived prestige and professional advancement are discussed in detail later for all gatekeepers. Last is the inertia on the part of gatekeepers to change, as they don’t experience the pain of the authors or the libraries that pour money into the publishers. This is a reason why bringing societies into closer contact with institutions is an important step in the process.

There is a growing imperative to change the role of for-profit publishers in the academic system, and not just publishing. Just like social media companies, publishers have realised that data can be gleaned from academics and that this can be sold as a commodity (Posada & Chen, 2018). Moreover, academics produce data that can similarly be captured and sold. There is an entire work-flow from grant applications through to publishing that is up for grabs and the big publishing companies are already in the process of acquiring the various companies (typically offered as free tools to academics like Mendeley, Overleaf, Peerwith, Authorea, etc.) that they need to capture, control and eventually dominate and steer the entire process (Brembs et al., 2021): what Pooley calls ‘surveillance publishing’ (Pooley, 2021). If we, as academics, want to remain independent of profit making companies (and in particular the big publishers), then we need to stop serving them now and move to open platforms (Racimo et al., 2022).

1.1.2.1 Perspective on the ethics of big publishers

One of the very real problems associated with large publishing companies is that their business model is to make the maximum possible profits for their shareholders. This means that they will invest wherever they feel that they can make the most money, irrespective of the ethics involved with such an investment. For such companies, this also includes promoting parts of their business that are involved with their investments. Elsevier is one of the big five publishers of scientific journals, but they are also heavily invested in oil and gas exploration and extraction (Westervelt, 2022; Dahl, 2022; Macmillan & Jones, 2022). This despite the fact that they are also publishing some of the best evidence that their own investments are causing irreparable damage to the planet: Advances in Climate Change Research Energy and Climate Change, Climate Change Ecology, The Lancet and many more titles that publish research on climate change. Moreover, Elsevier also publish 14 titles that aim to aid companies to extract more fossil fuels. It is not hard to see why increasing numbers of scientists are increasingly furious with Elsevier and have launched coordinated campaigns to boycott the company and highlight its hypocritical stance (visit: Stop Elsevier). Elsevier can change, and if they start to feel the heat from enough scientists, then they will - just as they backed down over the pricing of their content with German universities (Schiermeier, 2018). These are not the only problems with conflicts of interest in scientific publishing (see Part II) For other ways in which you can help stop the capture of science, see the Last Note.

1.2 Peer review

Few would argue that peer review is at the heart of publishing in science today. Consequently, there are several chapters in this book concerned with the subject: What is peer review; what to expect from your peer reviewers; how to respond to peer review with a rebuttal; and how to conduct peer review. The last chapter covers problems with peer review and this digs into some of the real biases that occur during peer review, and with the reviewers themselves. Peer review isn’t a perfect system, but in order to get the most from it we need to understand the weaknesses, both as authors and as reviewers. Only through this understanding can we reinvent the publishing system. We should not expect to do away with peer review (although this has been suggested many times in the past, and no doubt will be suggested again in the future), but by understanding the the biases that exist we will be able to make sensible choices despite the limitation.

Changes in the peer review system can make the difference between a highly biased system where editors manipulate the content for their own purposes (networks), or a system that is fair and equitable to all.

1.3 Impact factor

Impact factor is a simple metric, and as such there is no need for it to be anything more. But the publishers have managed to use impact factor to their advantage such that it has become of overriding importance for many publishing in the biological sciences today. But it doesn’t have to be this way. To make the most of the system, you will need a thorough understanding of the way in which impact factor can control other aspects of publishing, and how the behaviour of the editor can have a profound effect on the impact factor. A higher Impact Factor results in more submissions, and this in turn will mean that the editor will have more power over the content of their journal.

1.4 Citations

Sitting above peer review and Impact Factor in Figure 1.1 are citations. Compared to the other two parts of this wicked problem, citations seem to be blameless and without the potential biases of the others. However, citations are the units of control for Impact Factor and can be manipulated by both editors and peer reviewers. Metrics driven by citations are also at the heart of many of the problems in today’s publishing world.

The relationships between Citations, Peer review and Impact Factor are indicated with double headed arrows in Figure 1.1. There follows an attempt to describe these subtle differences, and the way in which they impinge on the gatekeepers at the centre.

1.4.0.1 Citations and impact factor

The more citations a journal gets (in the first 2 years following publication), the higher its Impact Factor. Higher Impact Factor journals will want any submissions that they choose to have a good chance of garnering as many or more citations than their current impact factor following publication. This can mean that if you have co-authors that are in active groups, publishing a lot, they are more likely to have their work accepted in higher IF journals (they are also likely to have more experience at science and publishing).

1.4.0.2 Impact Factor and Citations

The relationship flows in the other direction as the higher the impact factor of the journal that you publish in, the more likely your work will be seen, read and cited. Citations garner more citations, and your work bearing your name will become better known within your discipline impacting your chances of getting a job, being invited to give talks at conferences or at visits to departments.

1.4.0.3 Impact Factor and Peer Review

Your peer reviewers are likely to be directed differently depending on the Impact Factor of the journal. As the Impact Factor increases, so the Peer Reviewers will be asked about the novelty and impact (i.e. citations) of your work.

1.4.0.4 Peer Review and Impact Factors

The impact factor of the journal may well influence which peer reviewers are prepared to review your work. In theory, better read (usually more senior) reviewers will provide more insight and may well refuse to review for journals that they consider do not garner sufficiently interesting (novel and impactful) work.

1.4.0.5 Peer Review and Citations

Your reviewers are likely to look at the papers that you cite and this will inform them of the scholarly quality of your work. When you miss important citations, or omit contrasting viewpoints, you demonstrate a failure in your scholarly undertaking to read the literature.

1.4.0.6 Citations and Peer Review

Peer reviewers may well suggest citations for you to consider in your work. These suggestions can be legitimate attempts to increase the value of your work, and through these citations its visibility. There are also reviewers who will suggest that you cite their own publications, and even editors that suggest that you cite papers in their journal.

1.5 Open Science - a vision of the future

The way I advocate in this book is toward a vision for a future of Open Science (Figure 1.2). This future is both open and transparent. The transparency means that there is no need for this book, as there will be no hidden agendas or assumed knowledge needed for Early Career Researchers. Instead, it will be a ‘what you see is what you get’ system.

FIGURE 1.2: A simple schematic for an Open Science publishing model. Open science relies on the open nature of publication, communication and data. The gatekeepers still lie at the heart of this model, but are principally involved in ensuring the open and free flow of scientific information. This ideal world is free of the metrics that have dogged research in the past.

The simple schema for Open Science shown in Figure 1.2 is modified from O’Carrroll et al. (2017). The three areas of Open Science start with Open Data, the need to share both data, the code to analyse data, and the details for open source software with which to do the analysis all within open data repositories. The sector on Open Communication replaces the current closed peer review system with an Open framework where all actors are named and any interests declared. These include any journal gatekeepers (if involved). Lastly the publishing of the work is Open Access for other scientists and the public. This includes both proposals, preprints and published articles.

At the heart of Open Science publishing is ownership of the content. Like many aspects of changing the model from closed to open, implementation of the Rights Retention Strategy (see Janicke Hinchliffe, 2021), through mechanisms such as CC-BY, is available today. This is something that you, as an author, should insist on anywhere you publish. If the journal refuses, then think about what are they saying to you.

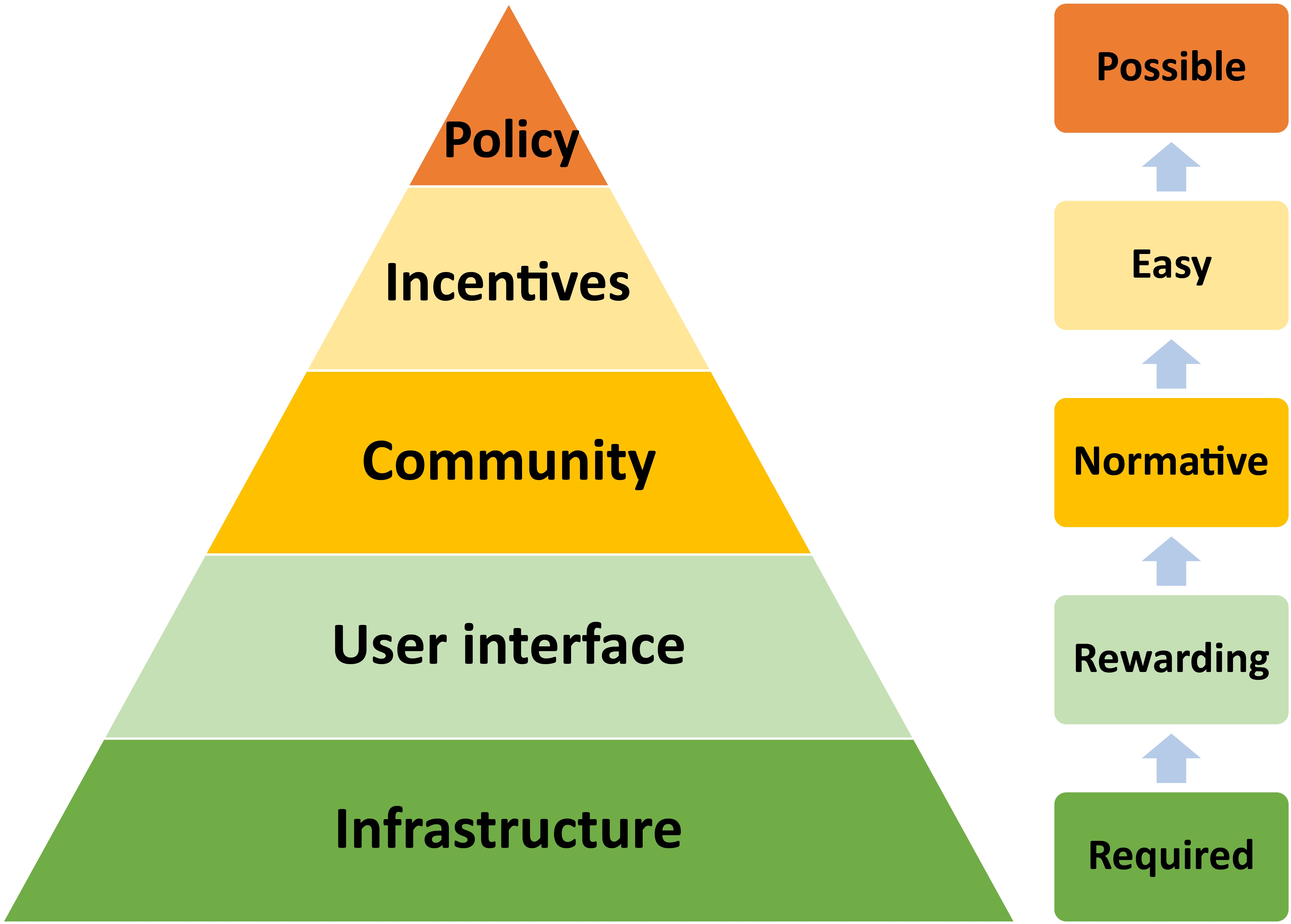

In my opinion, the Open Science framework is incompatible with the for-profit scientific publishing model that drives the current model (Figure 1.1). It can be hoped that the transition from Figure 1.1 to Figure 1.2 will be swift and happen within your career. However, the actors at play in this system are not neutral, and need both bottom up challenges (from yourselves as ECRs) as well as top down pressure (especially from large funding agencies). We should acknowledge that changing our research culture within science is not an immediate process, but requires a suite of cultural changes (Figure 1.3), that will start with early adopters and ultimately end with regulated policy (Nosek, 2019). These changes will be as exciting as they are challenging, and I hope that the contents of this book will equip you to participate fully.

FIGURE 1.3: Changing the prevailing culture in science will take time and effort, but is currently possible. This book attempts to provide information about how a change towards Open Science is currently both possible and easy (green), but requires widespread adoption among the biological sciences community in order to make it normative and rewarding (orange), until we reach ubiquity through policy (red) (Redrawn from Nosek, 2019).