35 Are you bullying or being bullied?

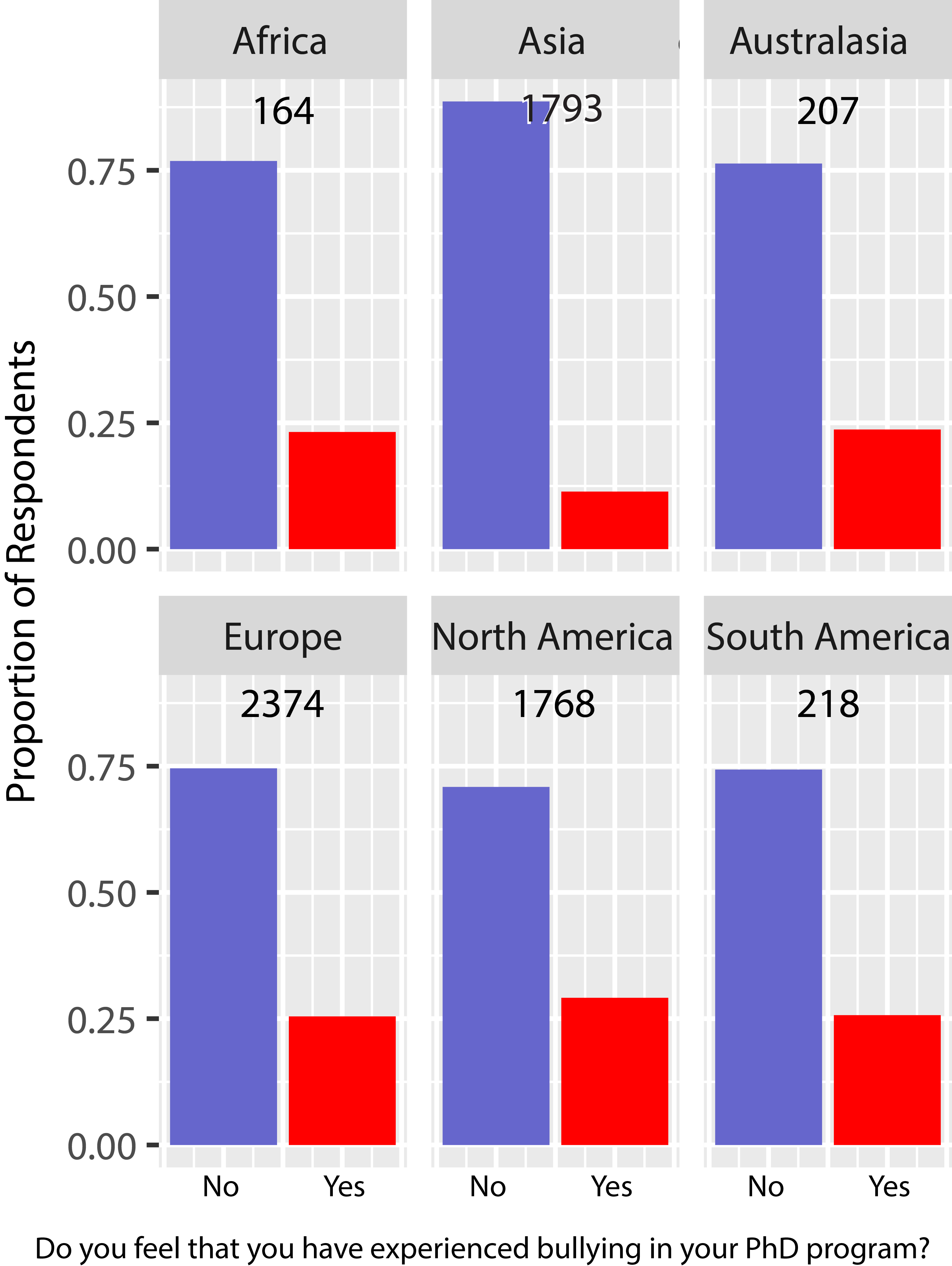

I am writing here about academic bullying because it is currently prevalent in academia, and because most of the bullies are unaware of what they are doing. In a 2019 survey of graduate students (see here Figure 35.1), 22% felt that they had experienced bullying during their PhD program. Bullying also happens in the most prestigious institutions (Abbott, 2019). The only way of improving the situation around academic bullying is for everyone to become more aware. It may not be happening to you, but it may be happening to people around you either in your lab or in another lab in the same department or faculty. If you think that this is very rare behaviour in academia, think again (Devlin & Marsh, 2018).

FIGURE 35.1: Do you feel that you have experienced bullying in your PhD program? Responses to a survey of graduate students (in 2019) demonstrates the changes in bullying propensity in different research cultures.

35.1 How to spot a bully

A bully is anyone who abuses or misuses their position of power in order to humiliate, denigrate or injure another. This does not need to be your advisor, or someone in your lab. It can be anyone in your working environment (watch the video here or here), including people in your institutes’ administration. These people are usually in positions of power with influence over you and your future. As in my example (see below) you may be worried that the power they have could be used by them to negatively impact your future. If you are worried about this, then their behaviour most likely conforms to bullying. Bullying often involves harassment that is designed to undermine your dignity, often through sexism, racism, or another prejudice (Krishna & Soumyaja, 2020). Even if you think that your bully didn’t mean to cause offence, the fact that they did upset you and that this behaviour was unwanted is enough to fulfil the criteria for bullying. Thus, it is not what they intended, but what you felt that is important in bullying. A direct consequence of this is that bullies often don’t recognise this as a description of their behaviour. It is worth bearing in mind that bullies are often damaged individuals who are repeating behaviour that they have themselves experienced from others. This doesn’t excuse their behaviour, but they may think that such behaviour is normal.

What you should ask yourself is if someone were to observe this behaviour from the outside, would they recognise the interaction as normal or see that something was not correct? Of course, if you observe this going on with someone else in your group, or outside your group, you should take the initiative to approach the person after and determine whether they feel like a victim: remember that not all interactions are as they appear from the outside. This is where a good set of institutional rules about bullying is important.

35.2 Bullying through peer review

Perhaps one of the most frequently experienced forms of bullying in academia is receiving unprofessional or upsetting comments during peer review (Beaumont, 2019). Often comments include direct ad hominem attacks on the authors, and this happens shockingly often (Eve et al., 2021). These problems with peer review have been covered in another chapter, so I won’t repeat them at length here (see Part IV). One of the ways in which peer review has sought to remove ad hominem attacks is through the double-blind reviewing system. When the identity of reviewers and authors is removed, this can remove many of the demonstrated biases in peer review, including biases against reviewers as well as authors.

Open Peer Review and the trend toward Open Science and transparency advocated in this book appear to undermine the need for double-blind reviewing as current systems have both author and reviewer (optional) names open at the point of peer review. Ideally, this system would be sufficiently monitored by editors such that reviewers with conflicts of interest are precluded from reviewing, and abusive comments are redacted. However, the system isn’t perfect and editors don’t always do the job that is required of them. This means that currently I think that there is a need for maintaining the system of double-blind reviewing and only once an article is published, providing the names of reviewers along with their reviews in a system compatible with Open Peer Review. This should, at the very least, be an option for authors within journals practicing an Open Peer Review policy. Currently, I know of no journals that actually do this.

35.3 What to do about bullying

35.3.1 In your institution

First, you need to find the rules that your institution has regarding bullying. If your institution has no rules, then they will need them and so helping them achieve this would be a good place to start (Mahmoudi & Keashly, 2021). No one wants to be the first case study, but there may need to be a first in order to set up a protocol.

Avoid the bully when asking for your institutional rules, but you should be able to find them via your departmental secretary, librarian, administrative support staff in the department or faculty. Read the documentation carefully and learn about how and by whom such reports are dealt with. Become aware of resources that are available; paritymovement.org is a great place to start. Read more about other people’s experiences and be aware that you are not alone (Malaga-Trillo & Gerlach, 2004; Mahmoudi, 2020).

Next, document your case. Make some notes about the incident(s), when they happened, what was said, how you were made to feel, and what power you feel the person has over you.

Share your burden with a trusted friend or colleague. It is worth sharing the incident with others to see what they think about your predicament. In the survey mentioned above, more than half of the respondents who said that they experienced bullying felt that they could not discuss their experience for fear of reprisals. However, you do not have to discuss it inside the workplace, and often it’s better to talk to people outside as the context is not so important in bullying. In your description, attempt to strip down the interaction into the component parts.

Follow your university’s rules about who to go to with your complaint. Don’t leave it to the next person in your lab to experience, they may not be as strong or as resourceful as you. It may not be your career that is destroyed, and the next student might not be so lucky.

35.3.2 During peer review

If you experience bullying through peer review, write directly to the editor handling your manuscript. Remember that they are often answerable to an editor-in-chief and an editorial board with a chair. If you don’t have any joy with your editor, then these other people can also be approached if you need to escalate your issue. A good journal will have an existing policy on abusive or bullying behaviour in peer review, so it would be good to search for this first.

35.4 What to do if the procedure against bullying at your institution doesn’t work?

My worst experience of bullying happened when I was a PhD student. It happened to me, and I witnessed it happening to other members of my lab. It wasn’t hard to spot. Students would come out of my advisor’s office in tears, and recount horrific stories of how he had debased and humiliated them. At the time, our department had no specific code on bullying, but there was a complaints procedure which started with the head of department. Unfortunately, as my advisor was also the head of the department, thus I could not follow the procedure as it was supposed to be done. Instead, I went to the academic who was responsible for postgraduates. The first two times, that staff member simply went to the head of department (yes, my advisor) and I was called in both times and bullied some more: how dare I complain about him?

The last time I tried to complain, once I had finished my PhD and felt much safer from the bully, I went to the dean of the faculty. He was the line manager of my advisor (still head of department) and was a lot more sympathetic. After listening to my story, and how my other lab mates were still suffering, he called them in one by one. And one by one they each denied all of the bullying that had happened. They were afraid. Unlike me, who had finished, they were still relying on their advisor to get their postgraduate degrees. The result was that without any corroborating evidence, there was no case for the dean to take forwards.

What should you do if the procedure at your institution doesn’t work? You become a survivor. You also become more vigilant against bullying in the future. Whatever happens, don’t be tempted to become the bully yourself. Support other survivors and make progress to improve the system for future postgraduate students. Bullying is in human nature, and it won’t stop. But we can make people more aware of it, and we can have procedures that work both for the bullied and the bullies.