9 Growing your network

During your PhD you will have had an advisor who would have been central to many of the decisions that you made. Don’t give up on that relationship, it is something that you have at the heart of your network. Therefore it is worth maintaining in the best professional relationship possible, as this is someone who you will need to go back to (probably lots of times) for references and other professional help. In short, always keep your advisor sweet. The same could be said about your thesis committee members, if you had one.

Having said this, as an early career researcher, you are now advisor-less, yet it is likely that you will still need advice from someone more experienced. Hopefully, there will always be your advisor, but the chance is that you may well have changed institutions, and so they may not be so close or easy to contact. This is a good reason for expanding your network by looking for a mentor to your role as an early career researcher. Increasing numbers of institutions are now recognising that early career researchers need mentors to advise them about how to move forwards within their academic field. Moreover, mentors can help promote equality and inclusively (Davies et al., 2021).

9.1 What to look for in a mentor?

The first thing to look for in a mentor is someone that you feel you are able to talk to easily. As you will see, there are a wide range of topics to discuss in terms of building your career, and you will need to find someone that you feel you can talk to about nearly everything safely and without fear that it might be used against you. The mentor should feel happy to talk and spend time with you. They should be someone that is genuine in their desire to help you and your career. You won’t have a fruitful relationship with someone that doesn’t really like you, or doesn’t want to spend time talking to you.

Next, your mentor should be someone who is already well established within an academic network that you want to (or already are) a member of. You will need to have common ground to talk about, and getting their advice on building your network will necessitate talking about how to manage others in the network.

The personal touch is nice to have, so if you can find a mentor who has an office in the same building, or on the same campus, then it’s great to be able to meet up and chat. However, your mentor doesn’t have to be in the same institution, or even in the same country. In these days of post-pandemic communication we are all a lot happier hooking up to meetings online.

If you still have choices, my suggestion would be to look for someone that you share non-academic interests with. For example, you may both enjoy playing squash together, hiking or scuba-diving. Meeting outside academia will make your mentor-mentee chats easier for both of you. Otherwise, try not to make your meetings with your mentor a burden on their work time. All academics are busy and core-working hours are hard to come by. Instead you could suggest taking your mentor out for a coffee or a sandwich during which you have your chat.

Note that a mentor doesn’t have to be someone that is particularly senior, although they should be well connected. Having said this, they are likely to be at a more advanced career stage than you.

9.2 Questions to put to your mentor?

Your mentor’s time is valuable, so always have an agenda when you go to talk to them. Have ideas that you want to pitch and get feedback from. Have some way of making notes about what they say, especially if you meet over a beer. You don’t want to have to go back and ask them again for the same advice. Be prepared to get the answer that they give. This seems an odd thing to say, but they may not always like your idea, and you should be prepared to listen to their advice whatever it is, not only when it agrees with your own ideas.

Typical things to discuss with your mentor are:

- Where to publish

- What meeting to attend

- How to extend your network

- Whether (or not) to write a reply or commentary on another groups’ work

- Whether to respond to a call for grant applications

- Whether to apply for a job

You may also want to share some of the more exciting aspects of your work, your findings and how you interpret them. Try to keep away from moaning about other academics, the amount of administration you have, teaching burdens, etc. Make your discussions as positive as possible so that your mentor is more likely to want to maintain and grow the relationship.

9.3 The importance of networks in your academic career

“Science can be described as a complex, self-organizing, and evolving network of scholars, projects, papers, and ideas.”

Fortunato et al. (2018)

There is clear evidence that researchers with good networks collaborate more, publish more and are better cited (Parish, Boyack & Ioannidis, 2018; Fortunato et al., 2018). Your mentor can be one way to increase your academic network. Perhaps more importantly, they can be a guide to help you through the network that you are involved with.

There is a good chance that you are already in a network where your advisor, and perhaps some members of your thesis committee, sit at the hub of an extended network that you have had partial exposure to during the course of your studies. If you haven’t realised already, these networks are of profound importance in every step of your academic career. Evidence from studies on the science of science (SciSci) suggest that within networks there is a great importance for small teams to disrupt science (Fortunato et al., 2018). In order to find team members (and for them to find you), you need to have a network of people to draw from.

Benefits of a good network include:

- increased citations for your work

- better chances that your work will be edited or reviewed by a member or an associate of your network, resulting in a higher chance of publication or a grant application accepted

- increased potential to be nominated for an award

- increased potential to be invited to give talks at conferences

- invitation to apply for positions and jobs in the labs of partners at institutions in the network

If you are already in a network, you should be thinking of ways in which you can get more from your network now that you are an early career researcher. If, on the other hand, you are not in a good (sizeable and supportive) network, you should be thinking about how to join an existing network or how to form a network around yourself and your work.

In many cases, managing your network is about providing opportunities for yourself and others in your network. There are many ways in which you can do this, but you should be prepared to put in a lot of work from your own side.

Potential initiatives include:

- writing a grant application that involves others in your network

- leading a piece of written work that includes others in the network

- a review

- a commentary on another article (not from your network!)

- a viewpoint or position article on an emerging topic

- organising a symposium aimed a central or emerging question within your network

- organising a special issue of a journal (potentially as a result of the symposium)

Your chosen mentor is the best person to discuss how to make waves in your network. Remember that relationships have already been forged in networks and you should never try to destabilise these. Instead, you should aim to become another node of the network by growing your own usefulness as a positive force for new and interesting initiatives that others will want to join. Because you are new, don’t expect to be included in every initiative. If you feel that you are being left out of other initiatives that you’ve heard about unnecessarily, ask your mentor whether or not it is appropriate for you to bring this up.

Always bridge and build relationships. As you should have become aware by now, there are many potential ways of becoming involved in combative elements of academic life. Your own sub-discipline will likely have groups of people that write commentaries about the work of other groups. Networks are powerful places to be, but they can also become destructive when another network opposes a position. I have seen this type of behaviour happen within and around my own limited subdisciplines. One group will publish a major finding in Nature or Science and a week or two later, the other group will publish a commentary pointing out what are (to them) flaws in the first group’s publication. I always have a sneaking admiration for those individuals that appear to swim between these groups, always maintaining good relationships with both sides. Theirs is really an interesting, but perhaps precarious, position.

If you feel that you don’t have any network, then I think that you should reassess your position. You likely do have people that you talk to and interact with that are already part of a network, but your question is how to increase the size, and potential scope, of your network. In the same way that everyone will have their own path through their career, the best way to grow your network will be unique to you.

9.3.1 Calculating the size of your network

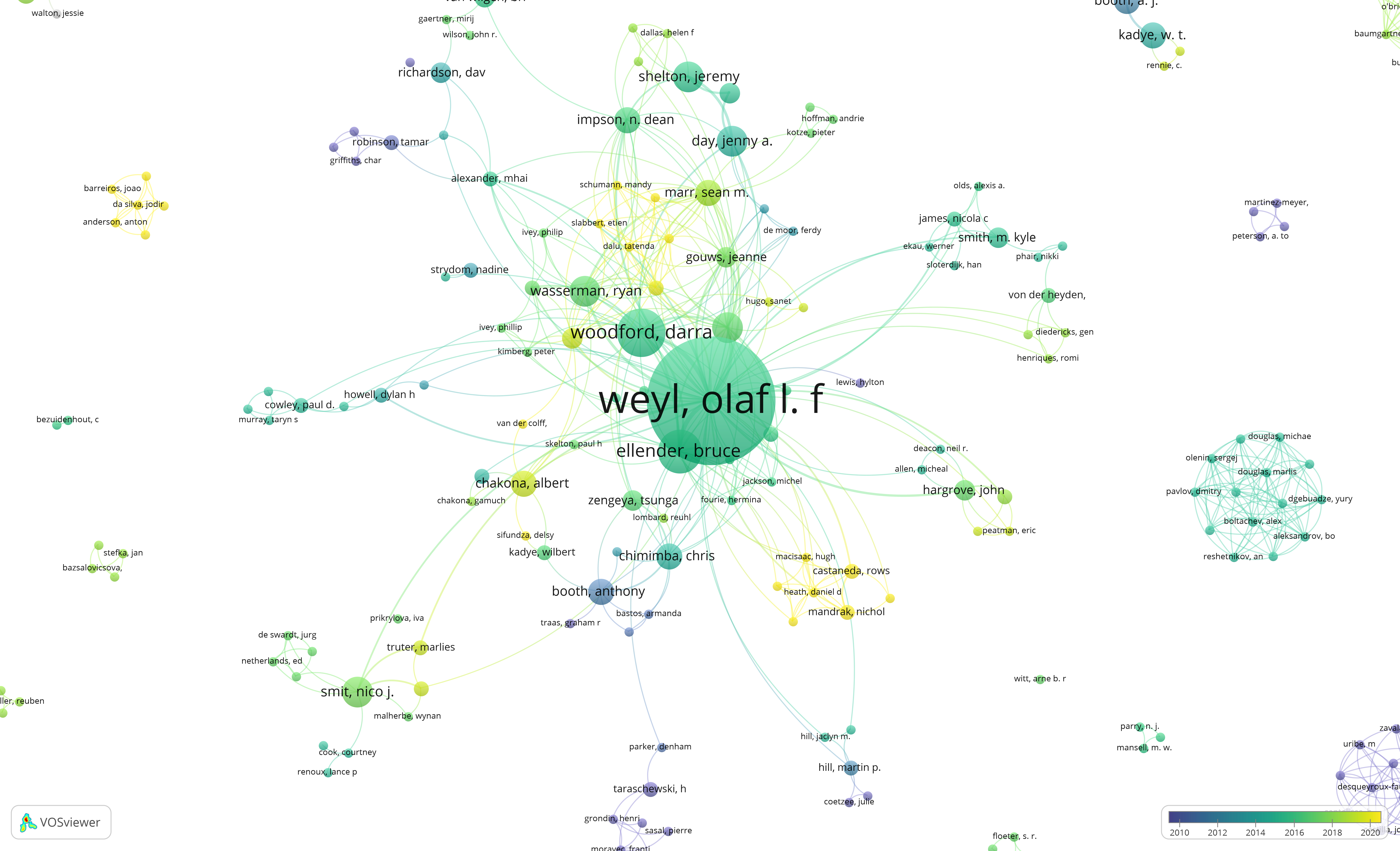

A simple metric for your network is the total number of co-authors that you have from all of your publications. Clearly, as you increase the number of people that you work and (hopefully) publish with, you will have a bigger, better functioning network. However, scientometricians have their own ways of interpreting and mapping networks (see Figure 9.1).

FIGURE 9.1: An author network for the Web of Science search for “Invasive fish” AND “South Africa”. In this author network you will see my friend and colleague, the late Prof. Olaf Weyl, who is at the centre of a large group of people who worked on invasive fish in South Africa. Olaf’s wasn’t the only research group, but certainly the most influential and joined up. Olaf’s collaborations were extensive, spanning continents and generations of researchers. Drawn with VOSviewer (van Eck & Waltman, 2010).

If you aren’t sure about who’s in what networks within your own researcher area, you can use appropriate keywords to download literature within the area that you work, and plot (using VOSviewer) a similar author and co-author network. I’d suggest using enough keywords to call ~1000 articles (including their citations) that include your research area (all or the majority of your papers should be included). Using a map based on bibliographic data, read the bibliometric files and analyse using co-authorship to describe the linkages between authors. This can be very revealing (see Figure 9.1), and while you should already be well aware of the big names in your area, some of the people that span areas and sub-subdisciplines might well be worth seeking out. When looking into their publications, ask yourself how they managed to span between networks (conducting a postdoc in each lab is one such way). More than this, you can use collaborations to combine networks of other Early Career Researchers in your subject area.

Another method for determining the size of your network, or those of potential collaborators around you, is to calculate your R value (Ioannidis, 2008). R is made up of two figures, I1 which is the number of authors that appear in at least I1 papers, divided by Np which is the number of papers that the author has published. I1 is a little like the H-index in that it increases each time you add a person in your network. For example, to have a I1 of 4, you need at least 4 publications in which you and the same 4 other authors occur. Parish et al (2018) show that as I1 grows, so the value of R decreases and researchers become most productive as R approaches 1.

Once you start to calculate your own value of R, you will appreciate that not only are large networks important, but that it is useful to start these networks early and maintain working with an every increasing group throughout your career.

9.4 Creating your own website

Whether or not you have your own lab as an Early Career Researcher you would be doing yourself a favour by creating your own website. Having a website is a way of creating your own brand and making you distinct from whatever institution or group you are a member of.

Websites don’t have to be fancy. There are plenty of ways in which to make good-looking websites using templates (Weebly, Wix, etc.). You can make these unique to you simply by using your own photographs. If you’re not a photographer then consider using some of the images from your work, or ask a colleague whether you can use some of theirs. Remember to place the most important keywords for your area in the website metadata so that it will pop up in any general web searches. There’s a lot of information out there on how to build a successful website that people can find, so I won’t go into this here.

What to include on your website

- Make sure that you have your professional contact details, including your institutional email address. This will help any editors for other colleagues that are trying to contact you. Avoid having a form as the only way of making contact with you.

- Write some general blurb about yourself and your work including all relevant keywords for your subject area. Three to four sentences on what you do is really useful to be able to quickly send to people for a bio about yourself. Once you are happy with your blurb, place different length blurbs on your website so that you can quickly respond to requests for 50, 100 or 200 words.

- Have a list of your publications, conference presentations, popular articles, patents, and any other outputs that are relevant to your professional profile.

- Provide a summary of your professional research experience listing where you did your degrees and any post doctoral work. A kind of mini-CV.

- Make sure that your website works on lots of different platforms. Preferably it will work on mobile devices as well as desktops and laptops.

- Link to your various academic profiles: Publons, ORCID, Scopus, ResearchGate, Academia.edu, GitHub, etc.

- Provide a link back to your institutional website and your current lab, as this will help legitimise your independent website standing. People want to see that you are who you claim to be

Optional items

- You could write a blog

- You could have short articles about some of your publications

- Downloadable version of your CV

- Future plans for projects

- Collaborator page - with links to collaborators in your network

- Data from projects (e.g. images, sounds, videos, R code, etc.)

Things to avoid

- Be careful about mixing personal and professional profiles

- Don’t provide links to any personal social media accounts, only professional ones

- Don’t allow your site to be too static (static sites rank lower in search results)