5 What can you publish?

As you become more and more familiar with the academic literature you will quickly realise that actually you can publish just about anything. In this part of the book I’m going to talk about some of the most common articles that you can get published. But don’t feel constrained by what you see here. When it comes to publishing you’re only constrained by your imagination.

As an early career researcher, you will have a body of work from your thesis that you may have already published, or be in the process of publishing. These likely contain a number of data chapters that will be published as a series of papers in scientific journals. However, it’s worth reflecting here about what it is possible to publish and how this might complement your existing and future publications, as well as increasing your publication portfolio with which to further your career. Although publishing is not the only way to do this, having more publications is likely to increase your visibility in your community, as well as giving you more practice in academic writing.

5.1 Standard articles

You should already be familiar with the concept of publishing standard articles and you may already have a number of these published both as a first author and as a co-author. As an Early Career Researchers, you should consider what and how you publish. For example, you should consider whether or not publishing more articles is always the right strategy for you. You will find a chapter that discusses this concept in detail in Part IV. In particular, you should be aware of the concept of salami-slicing a standard article into two or more different papers.

5.2 Reviews

When considering the way in which citations work one of the things that you should notice is that reviews and in particular meta-analyses are cited many more times than most individual papers. For this reason one of the best things you can do is an early career researcher is to author a review on the topic of (or around) your thesis, or even better a meta-analysis.

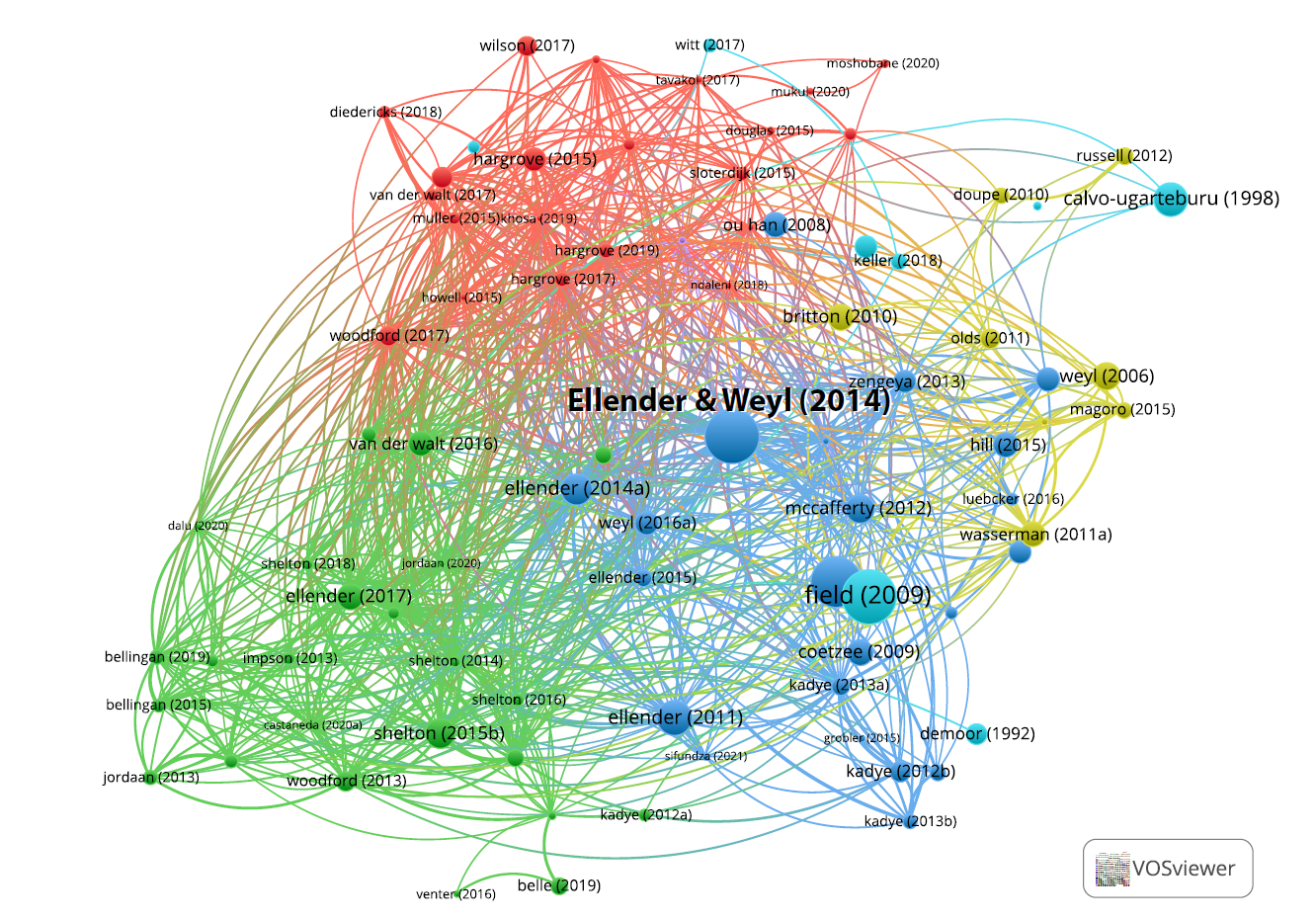

I provided an in-depth chapter on how to approach writing a review including different aspects of meta-analyses in another chapter of this book. The importance of a timely and much used review can be seen in a lot of citation maps such as in Figure 5.1. In this example, Ellender & Weyl (2014) was the first comprehensive review that sums the knowledge to that date on invasive fishes in South Africa, and so was cited most times that anyone published anything on invasive fish species in the country thereafter. Because this subject was the focus of a lot of research that happened in the area, you can see that it would logically sit at the centre of this subdiscipline. If you are unsure about whether or not a review is needed in your subdiscipline, then constructing a citation network based on the key-words in your subdicipline, such as that in Figure 5.1, might well be useful.

FIGURE 5.1: A timely review can be at the heart of a citation network, such as this one on “Invasive fish” AND “South Africa”. In this citation network, you can see that the best cited paper (largest circle - green and centre) is a review by Ellender & Weyl (2014). It has good connections with all of the three subject areas of this citation network, and although it was published in 2014, by 2021 it had been cited 111 times. Drawn with VOSviewer (van Eck & Waltman, 2010).

5.3 Natural History observations

Natural history notes are effectively publications made from unplanned observations. They underpin many of the Big Ideas in biological sciences, including the theory of evolution (Darwin, 1859). For an insightful read on the interaction of ecology and natural history, see Anderson (2017).

Natural history observations are accounts of novel information, once-off or multiple/methodical observations and range from a full paper to a few structured paragraphs. They are defined by not being the outcome of a planned experiment or inquiry. That is, they would not be part of your research proposal or preregistered plan for your research. This does not make them any less important than one of your planned studies, but statistically they generally have less power and could potentially be victim of HARKing. As a result, it is important to clearly state in the Methods that they are natural history observations, so that others know how to interpret them.

Important natural history observations require replication as planned experiments to determine their validity and hence importance moving forwards. They are a good example of how preregistered plan for your research do not overly restrict publishing your work, but do keep you honest in your reporting.

5.4 Commentaries or Opinion pieces

Your opinion is important, or at least as important as anyone else’s. Critical reading is a very important part of science and something that you should maintain throughout your career. From time to time you will come across articles and papers that you know are wrong, or fail to represent sufficient balance. Many journals will accept commentaries (also known as rebuttals) or opinion pieces based on articles that they have already published. This is an opportunity for you to make a correction to something that’s already published in the literature. Please know that here we are not talking about anything you think might be fraudulent for that there is another process.

There are several things worth considering before putting pen to paper on your commentary and sending it to the editor.

If the people that wrote the article are in your network when a network close to yours then consider approaching them first about what you see as their error. You may end up getting along with them much better when you seek a solution together than writing something that antagonises them. Even if they aren’t in your network you may find a way to increase the influence of your network through soft power instead of with a commentary.

A commentary should never be an ad hominem attack. Never comment on the authors, only their content.

Check with your mentor or another colleague that your interpretation of their error is correct and that pointing this out will have some value. Always try to do more than just say: “no it isn’t”. Many journals won’t be interested in a commentary that does nothing more than show an error. If possible try and include some original data or some original analyses in your response.

Remember that your commentary will likely be sent immediately to the authors that you’re commenting on before it is accepted by the editor. This means that they will also get a chance to comment on your commentary. However you will not get a chance to look at their comment.

Have a look through at some instances of where this has happened in the literature in your field. If you can talk to the people involved and try to find out whether things worked out positively for them. Although I do not want to say that you shouldn’t do this, you should know that what you’re doing is not going to backfire on you especially as an Early Career Researcher.

If you do decide to go ahead with this then consider asking other members of your network to join you. Although it’s not a sheer game of numbers it may help you to gauge a better and more equitable stance on your commentary.

Don’t expect that your rebuttal will change the way that people think. A study of seven prominent papers and their rebuttals showed that rebuttals were rarely cited alongside the prominent paper, and most citations were not critical (Banobi, Branch & Hilborn, 2011).

The other option you have is publishing a commentary that is very positive about the findings of a particular paper. Some journals published such commentaries about the contents of their journal as well as the contents of journals outside. Again this may be a better way of influencing soft power.

There are also lots of possibilities about publishing pieces on what it is like to work within your area of the biological sciences. This could be about towards your experience as an early career researcher, but may take on just about any stance that you feel is important in your area of biological sciences (e.g. language, covid, racism, colonialism, etc.).

5.5 Letters

These are generally very short pieces that you can write, often to high profile journals with letters pages. They can be used to raise the profile of all sorts of issues within your subject area or profession.

Letters are going to have to be super polished and concise in order to get your point across in very few words.

5.6 Editorials

You are unlikely to be able to publish an editorial without first being an editor, but there may be a potential for you to become an editor, associate editor or junior editor in a number of society or publishers’ journals. Once in position, the editorial is a powerful place to launch your opinion to subscribers.

There are such things as guest editorials for special issues and special issues are particularly useful if you are an early career researcher. If you want to edit a special issue of a journal in your area then approach the editor well and advance of when you want to do it (possibly more than a year in advance). It’s often good to have these things linked to an event like a symposium that you are organising.

Once all the contents of the special issue are in you can put an editorial together to explain what the idea was of the symposium and co-authored along with your other symposium organisers. Special issues of symposium often get cited more than other articles just because it is a collection of similar things altogether in one place.